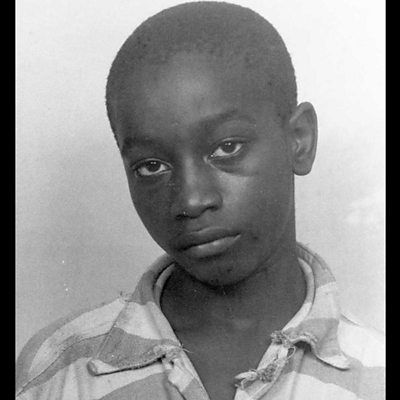

In Just 80 Days…The Short Story of George Stinney

- Tammy Lee

- 4 days ago

- 5 min read

George Junius Stinney JR was born on the 21st of October 1929 in Pinewood, South Carolina. He and his family lived in Alcolu, a small town where white and black families were still segregated, and racism was rampant (unfortunately common for Southern towns at the time). Railroads ran down the middle of the two sides of town.

On the 23rd of March 1944, a search was underway for Betty June Binnicker, who was 11 years old, and Mary Emma Thames, who was 7 years old; two young girls who had gone missing from the ‘white’ side of town.

Tragically, both of the children were found dead, with the cause of death having been ‘inflicted by a blunt instrument with a round head, about the size of a hammer’ (from the medical examiner’s report). The bodies had been discovered on the ‘black’ side of town, and it was now a murder investigation.

The two girls had last been seen riding their bikes together. They passed the Stinneys’ home and asked George and his sister Aime if they knew where to find maypops (slang for passion flowers). Aime later said that she was with George after this interaction, including the time that the police believed the murders had taken place.

Despite no evidence, George and his older brother were arrested on suspicion of murder; John was released, but George was kept in custody. The only reason for keeping George in custody was a handwritten statement from his arresting officer, County Deputy H. S. Newman. It read:

‘I arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney. He then made a confession and told me where to find a piece of iron, about 15 inches where he said he put it in a ditch about six foot from the bicycle’.

No one else was a witness to this ‘confession’.

Following George’s arrest, his father was fired from his job at the sawmill. This meant his family also had to vacate their home, which was provided as part of the job.

During this time, George was being detained at a jail 50 miles away and being interrogated. He had no counsel or contact with his parents (who wouldn’t see him again until the trial).

The trial was on the 24th April 1944. George’s court-appointed counsel did not attempt to defend the child in front of the all-white jury – even when the prosecution gave two different versions of George’s ‘confession’. There was also no written record of George’s ‘confession’, apart from Newman’s statement.

While the trial was going on, more than 1000 white Americans entered the courtroom to watch the proceedings; black people were denied entry. It only took the jury ten minutes to find George guilty of both murders, despite there being NO evidence, and the prosecution's inability to keep their story straight. No appeal was filed, and Judge Phillip H Stoll sentenced George to death by electric chair.

There were people (black and white) who were horrified at the case, and especially the death sentence given to such a young boy, a child, and urged Governor Olin D Johnston to step in.

Johnston visited George in jail on the 14th of June. He wrote to the people who were asking for George’s release, saying:

‘I have just talked with the officer who arrested in this case. It may be interesting for you to know that Stinney killed the smaller girl to rape the larger one. Then he killed the larger girl and raped her dead body. Twenty minutes later, he returned and attempted to rape her again, but her body was too cold. All of this he admitted himself.’

He denied clemency, even though what he had written was nothing but lies, as shown by the evidence of the autopsies. Apart from some slight bruising on Betty’s genitalia, there was no sign of rape or sexual assault.

On the 16th of June 1944, George was led to the electric chair. He was too small, at 5 feet 1 inch and 90–95 pounds, and had to use a Bible as a booster seat. The executioner placed a strap over George’s mouth (which did not fit), and the child started sobbing with fear. He had no last words, and at 7.30 am, George Stinney was executed; the mask slipped when the electricity hit him, and you could see tears running down his face. He was 14 years old. He was buried in an unmarked grave at the Calvary Baptist Church Cemetery in Lee County, South Carolina.

In 2004, George Frierson began researching the case, and his work attracted the attention of lawyers Steve McKenzie and Matt Burgess. They aided him in his research (which was difficult as there was, shockingly, no transcript of the trial) and in 2013, along with attorney Ray Chandler, they filed a motion for a new trial.

The Civil Rights and Restorative Justice (CRRJ) said:

‘There is compelling evidence that George Stinney was innocent of the crimes for which he was executed in 1944. The prosecutor relied, almost exclusively, on one piece of evidence to obtain a conviction in this capital case: the unrecorded, unsigned "confession" of a 14-year-old who was deprived of counsel and parental guidance, and whose defence lawyer shockingly failed to call exculpating witnesses or to preserve his right of appeal.’

The court hearing was in January 2014. This time, George’s siblings were allowed to speak (They had been denied the ability to provide alibis during the first trial) and stated that George had been with them at the time of the murders. The Reverend Francis Baton, who initially found the children’s bodies, said there was very little blood around the area, suggesting that they were murdered elsewhere before being placed over the border. Wilford Hunter, who was in prison with George, testified that George told him he had been forced to confess and always maintained his innocence.

Judge Carmen Mullin dismissed George’s guilty conviction, ruling that he had not had a fair trial, that his confession was more than likely coerced and that the execution was cruel and unusual punishment. She wrote,

‘No one can justify a 14-year-old child charged, tried and convicted in some 80 days’.

The family of Betty Binnicker and Mary Thames never doubted that George was guilty.

In January 2022, South Carolina state representative Cezar McKnight introduced a bill, the George Stinney Fund, which would make the state of South Carolina pay $10 million to the families of the wrongfully executed if their conviction is posthumously overturned.

There have been discussions, rumours and theories over the years as to who was responsible for the murders, some more likely than others. I don’t believe George committed murder. Personally, I think that three children were murdered during this time, but one murder was considered to be legal. On that note, thank you for reading, please take care of yourselves and fuck racism.

Hi! I spend a lot of time writing for the website, and I basically exist on caffeine and anxiety - if anybody would like to encourage this habit, please feel free to buy me a coffee!

Comments